I was able to fit in one more trip before Christmas and went to see how my friend Maribel was getting on with her new house in Algeciras, in Andalucía where she comes from. It needs quite a bit of work but it’s solid and has parking. Unfortunately none of the furniture, fridge, stove, coffee machine, etc. that she bought on Black Friday had been delivered so it was pretty basic but I went there to see her not to admire Spanish interior design. I had a bed, bedding and hot water. That’s a good start.

It was 22 degrees when I landed in Malaga on December 5. Like a British summer’s day. The light on this stretch of coast is extraordinary and makes the waves sparkle like jewels. The huge beaches were deserted except for a few hippies in the beach-side shacks at the entrance to the beach at Tarifa. An eagle flew over the car on our way there, but it didn’t impress Maribel at all. A few days later I saw why when she took me to an artist’s settlement, Castellar de la Frontera, high in the mountains where a convocation of more than 100 eagles was circling over the ruined castle and village. (I counted them on my photographs) I had always assumed they were solitary birds, but these were real eagles, as confirmed by the locals, and may have been gathering to migrate. I later found that in Tarifa you can sometimes see as many as 20 raptor species in a single day, it is a paradise for bird watchers. I’m told that the Spanish Imperial Eagle, which is very rare, can be seen there thanks to a conservation programme.

The beach at Tarifa is enormous and continues for more than 10 kilometres. It is hard to imagine that it could ever be full, and in fact in the section we were in there were few facilities for tourists beyond a couple of small beach bars. Most of the beach is in the National Park and is protected from development. It really is magnificent, the ultimate beach with soft golden sand with a very special light coming off the sea. Of course sunset over the beach is quite spectacular and everyone sits down to watch it. Not that there were that many people there to do so.

Once the sun has gone down and it has grown dark, the closeness of Africa becomes apparent. Glittering across the Strait you can see streetlights and car headlamps in Morocco which is only 14k away at the Strait’s narrowest point, separated by one of the most treacherous meetings of seas in the world as the Atlantic meets the Med. Even in the day, the outline of the hills of Cap Spartel are visible outlined above the sea mist.

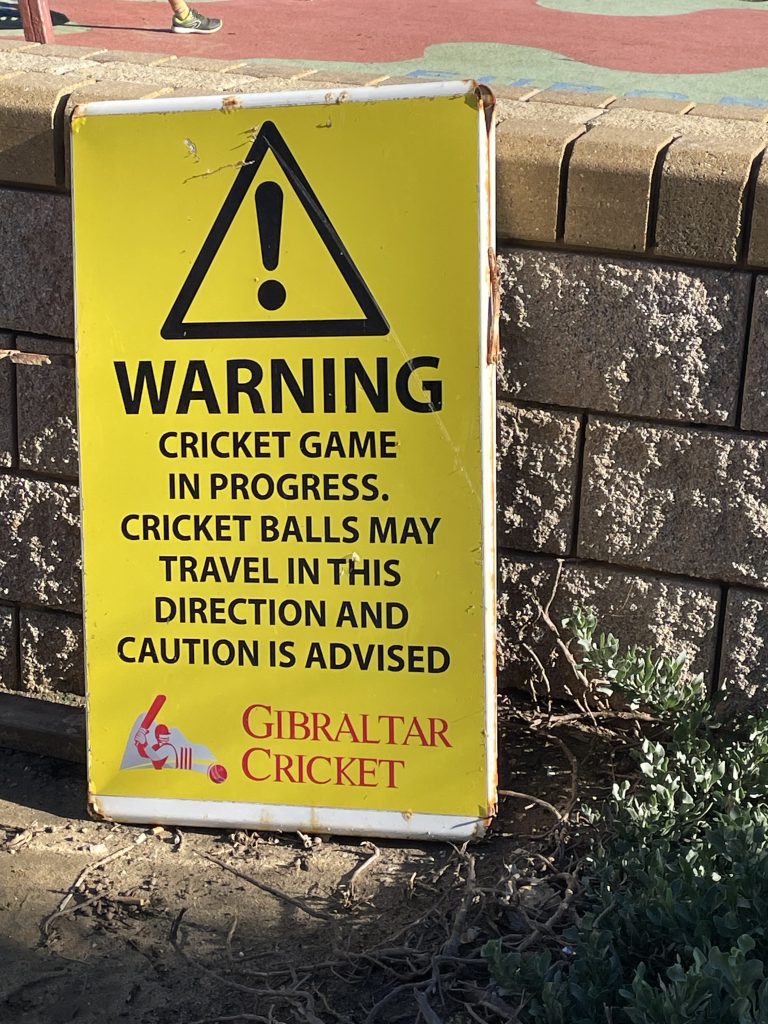

I had not realised how separate Gibraltar was, sitting out on its peninsular, directly across the bay from Algeciras. To enter requires all the business of passports and security checks that you get at border crossing all over the world, but once you are there, it is like crossing through Alice’s looking glass. Suddenly, in the Mediterranean sun, you have red phone boxes, British style number plates but with GBZ or the post-Brexit GIB prefix, loads of Range Rovers filled with middle-class couples who look like they belong in Chalfont Saint Peters. There are pubs, filled with badly behaved British children, their mothers quaffing white wine rather than afternoon tea, and a High Street that belongs in somewhere like Cheltenham circa 1975. And towering 470 meters over it, sits the rock itself, a spectacular cliff face, honeycombed with tunnels and doubtless containing multiple gun emplacements, aimed at the Strait, which is why the British captured it from Spain back in August 1704. It doesn’t take long to see as its only 2.6 square miles – 6.7 km2 – but the views are wonderful. We wandered in a small graveyard where tombstones recorded officers from Nelson’s flagship at the Battle of Trafalgar, shaded beneath giant olives and eucalyptus. It is the other, secret, end of British military might: there are battlements, gun emplacements and defence towers of all ages everywhere. It evoked poignant feelings, a weird set of childhood images from the world of British colonial power that I was taught in school in the forties and fifties that is virtually, fortunately, all gone. I remember at primary school being told at morning assembly that we should no longer refer to the ‘British Empire’ and instead say ‘the British Commonwealth’ though what event prompted this I can’t say as I was only about nine years old and the Commonwealth has existed since 1926.

As Tangier was just across the water it seemed silly not to go. In fact, I had booked hotel rooms at the El Muniria for February and wanted to see the hotel again as they seemed just a bit too cheap at 25 euros for a room with en suite bathroom. And they were. The El Muniria, where Burroughs had lived, and where Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky also stayed, is next door to a building site. They were drilling the last remaining fragments of the adjacent building when we arrived and we could only speak to the receptionist in between bursts of drilling. Presumably by the time we arrived in February, construction on a new building would have been well under way. No way could we have stayed there. We retreated to the El Minzah for a bland, international hotel-style glass of wine.

In the Medina we peeked down the alley where Burroughs used to live in Tony Dutch’s male brothel, but we were regarded with such suspicion that we rapidly retreated back around the corner to the Petit Socco where Burroughs used to pass the time of day with Kiki. Here they are in 1954, and how it is now, 70 years later.

There are frequent mutterings in Spain about the sovereignty of Gibraltar, but it is very convenient for the local rich people – of which there are a great many – for it to remain British. Also, the port of Algeciras is the largest in Spain, and the second largest in the Med. Over three million containers pass through it each year and many of them are filled with drugs, smuggled goods and sometimes even human cargoes. The local mafia is very powerful and they, too, like the proximity of all those British banks down Gibraltar’s Main Street.

Of course the food in Algeciras was fabulous and incredibly cheap. This is a working town filled with working people who appreciate good food and wine: Pulpo con mayonesa – 2 euros; Pollo salsa, 1.5 euros; Calamares 2.2 euros; Boqueróns – 2 euros. Oh, and very large glasses of wine at 2 euros. About a quarter the price of the same in London restaurants and ‘tapas’ bars and of course much fresher. They are not paying London rents, nor London wages, and the fish was landed that morning. We went to a number of bars. Maribel seemed to know people in all of them. Most people stand – being old I usually got a stool or, if I was lucky and they had one, a chair – and watched the show. They shout in Andalucía, even when their faces are inches apart, and there is a great deal of play acting. They start a sentence, or make a statement, then repeat it in order to get going, getting louder as they reach the main content of their argument at the top of their voice but they are polite, they will be quiet while their protagonist speaks, again using the same formula. This speeds up, to and fro, with a lot of laughing and dancing about. It is a largely blokey thing; I didn’t see many women in the bars but there were some.

And so to Paris where I stayed with my old friends Catherine and Steve in Sud Pigalle, or ‘soupy’ as it’s known (Sud Pi). Catherine and I saw the Mark Rothko show at the Fondation Louis Vuitton and, though I normally hate blockbusters, this one was great. The exhibition contains 115 works so we hurried through, then returned to see the most interesting ones. The first two rooms are all figurative – and of figures – and show the early use of his colour palette. He was clearly influenced by Arshile Gorky in his pre-abstraction work. Then we reach his wonderful mature style, vibrating blocks of orange, red, magenta on colour saturated grounds, mostly made between 1947 and 1958. Some of my all-time favourites were there. LVF have brought over the 1959 Seagram series from the Tate. These nine paintings were commissioned by the Four Seasons restaurant in the Seagram Building in New York but after disagreements (they wanted brighter happier work) he kept them for himself and in 1969 bequeathed the nine paintings to the Tate so that they could be near his beloved Turner’s works. He made 30 pictures in the series all together and offered them all to the Tate but director Norman Reid declined, citing ‘storage problems’. Another typical Tate blunder; in 1921 the Tate turned down a gift of Cezanne’s ‘Mountains in Provence’ as ‘too modern’.

As the work continues it gets darker, more depressive until we reach his 1969-70 ‘Black and Gray’ series which are just that, canvases divided equally into black and grey. Then he committed suicide. It was uncannily like the Nicolas de Staël show held at the Musée d’art moderne this summer in which the paintings became more and more depressing and lifeless, as they led to his suicide. But here one can go back to the glorious ‘light’ paintings, the reds and yellows whose colours move and change the longer you view them. It was not too crowded so we were able to study them properly. It’s on until 2 April 2024.

Finally, it’s that time of year again. Here’s my son Theo dressing the tree. Happy Crimble.

And let’s not forget: from the river to the sea.