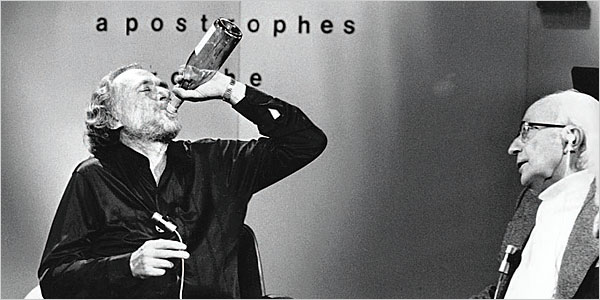

- Message in a bottle: Charles Bukowski on the French television show “Apostrophes” in 1978.

By Ron Powers

Published: November 19, 2006

“The unexamined life is not worth living,” Socrates used to mumble after a long night of throwing back hemlock. A readerly crawl through the booze-babe-and-brawling saga of Henry Charles Bukowski Jr. tempts similar skepticism about the examined life.

A half-century’s worth of scrutiny — most of it from Bukowski himself, but more recently from a succession of biographers and scholars — has dissected what seems like every moment of the writer-poet’s 73 years until his death from leukemia in 1994: his childhood thrashings by a brutish father; his decades of willfully impoverished rooming-house life in the Los Angeles underbelly; his nearly constant drunkenness; his bar-fights; his arrests; his whoring; his volcanic feuds with editors, friends and the women who dared take up with him; his liquor-induced hemorrhages and vomiting spells and apartment-smashing rampages; his years of nocturnal drudgery as a postal worker; his self-loathing and his often suicidal despair.

Was this life worth living? Perhaps only if one reckons with what Bukowski’s examinations of it produced: the brutal, profane and darkly hilarious art that held redemptive power for legions of his readers. Bukowski’s skeletal, self-referential poems and stories, barren of metaphor but crackling with hard truth told in American barroom vernacular, brought him adulation from people who scarcely read what Bukowski called “lacy” poetry (he used a noun other than “poetry”). But the adulation came late: he did not enjoy fame beyond the Los Angeles demimonde until he was 47; his work did not begin to earn him significant money for another 12 years.

When the spotlight finally found him, “Hank” Bukowski became a worldwide celebrity to poets and scholars of the craft, as well as to the dispossessed and would-be dispossessed who gorged on his isolato spleen. His published poems, a fraction of the tens of thousands he scribbled through his squalid decades, sometimes on newsprint, were collected in more than 40 volumes and translated into several European languages — “Notes of a Dirty Old Man,” “Love Is a Dog From Hell,” “South of No North,” “The Last Night of the Earth Poems” and others. Norman Mailer and, later, Sean Penn hung with him. Women flew to Los Angeles from around the world to bed him, ignoring (or digging) his beer-belly and pockmarked simian face that “hung down between his shoulders, giving him the appearance of a massive troglodyte,” as one acquaintance described him. He has been the subject of a dozen-odd biographies and critical studies, and has been portrayed twice in movies: by Mickey Rourke in 1987’s “Barfly,” and by Matt Dillon in last year’s “Factotum,” based on one of Bukowski’s five novels.

So what’s left to examine?

Not much, alas, judging by his latest biographer, Barry Miles, in “Charles Bukowski.” Miles, a British bookstore owner in the late 1960s who has written studies of three other Beat-era luminaries, offers a serviceable retelling of the poet’s life. The book is bolstered by material from Bukowski’s bruise-covered childhood and his befogged bus-riding young manhood that other biographers have scanted. Miles is a knowledgeable admirer of his subject and a decent critic of the work. His book provides morsels — bloody, beery, bathetic morsels — for those with insatiable appetites for Bukowskiana.

Yet in this very morseling lies the nearly insurmountable challenge. Miles is competing, in the reconstruction of Charles Bukowski, with Bukowski himself. Virtually all the writer’s poems and novels are examinations and re-examinations of his life as he lived it. And imagined it.

Miles recognizes this challenge. He laments early on that Bukowski’s constant self-mythologizing makes it “impossible to sort out truth from fantasy.” “This is the problem with deciphering Bukowski’s stories,” he goes on. “He claimed they were 95 percent accurate, with embellishments here and there. The percentage is probably closer to 50 percent fact, 50 percent fantasy.”

This ambiguity, however, seeps into Miles’s account: he rarely seems to know, or very much care, whether a given incident is fact or fantasy. (His “Index of Sources” reveals that he relied almost completely on previously published information.) Though he sometimes troubles himself to question the accuracy of a poetic Bukowski anecdote, or dig up a contravening version from other secondary published reports, Miles is too often content to let the writer’s work stand for the historic record. Of a poem describing Bukowski’s careless disposal of his late father’s property, Miles muses, “The details are too accurate to have been imagined so something like this must have happened.” Of a certain well-recounted incident regarding unintentional sodomy: Bukowski “repeated the story in a number of forms and mentioned it in letters so it, too, has a basis in truth.”

This passive approach to fact-gathering can pose a problem when, as often happened, Bukowski produced five or six versions of an incident over a period of years. Miles typically resolves this by pointing out that there are multiple variations.

What we are left with, then, is a kind of abbreviated paraphrasing of a life that — absent its digestion into art — was almost repellently debauched. Since Miles curiously offers hardly any examples of Bukowski’s poetry, he is in a competition that only his subject can win. Why bother to read the biographer’s endless prosaic variations on “He drowned himself in alcohol” when we have access to the master’s own testimony: “I drink and cough like some idiot at a symphony / sunlight and maddened birds everywhere / the phone rings gamboling its sounds / against the odds of the crooked sea / I drink deeply and evenly now / I drink to paradise / and death / and the lie of love.”

That passage, not coincidentally, may be found not in Miles’s book, but in a much more evocative work published in 1999 by Miles’s countryman Howard Sounes. “Charles Bukowski: Locked in the Arms of a Crazy Life” is about the same size as Miles’s study. Yet by choosing to compress the childhood and young manhood, Sounes leaves room for rich testimony from those who knew the poet and, crucially, for the poetry. His acknowledgments show exhaustive primary research: interviews with more than a hundred of Bukowski’s friends and relatives in America and Germany, including Allen Ginsberg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. An even more fertile source was John Martin, whose Black Sparrow Press became Bukowski’s most important publisher. Martin allowed Sounes access to 27 years’ worth of unpublished correspondence between him and the poet. Sounes also tracked down the true version of many Bukowski stories — his arrest record, for instance — from information available in public documents. Miles leaves most of this material unexamined.

Miles can rise to wonderfully moving arias in the rare moments when he chooses. “If he felt like a night out,” he writes of Bukowski’s early rooming-house days, “he would head over to the medieval carnival of Main Street with its frenzied night-time action: three-feature movie houses ablaze with neon; burlesque joints with photographs of impossibly well-endowed women … shoeshine stands where the bootblack could direct you to anything in the world you could want, legal or not; jukeboxes blaring from bars filled with young male hustlers … and the vice squad wagon cruising the streets around Sixth and Main, where the transvestites gathered. … The long, narrow bars jammed with humanity, broken neon flickering outside reflected in the smeared mirrors, the peeling plaster yellow from nicotine, the booths slashed and patched … pawnshops filled with suits and rings; army and navy surplus stores … the walls dripping from the steam tables; liquor stores … and, above it all, the black, starless, Los Angeles night.”

Barry Miles perhaps should examine this lyric touch of his more deeply and more often. After all, as his subject said about writing, “often it is the only / thing / between you and / impossibility / no drink / no woman’s love / no wealth / can / match it. / Nothing can save you / except writing.”